Restorative Justice as an Alternate Form of Discipline

Once upon an elementary school, you may have reveled in a sense of justice. When Tommy maliciously knocked over your block tower in second grade, he was made to apologize, and perhaps helped rebuild your tower. When a long term feud spawned between you and Susy in fifth, a catalyst was identified with the help of a school counselor. You both were given the tools to make amends. Now, during your senior year, when Matt calls you a homophobic slur to your face, the so called “disciplinary actions” could be described as lackluster. The administration assures you that high-profile “investigations” are taking place, yet you see him laughing down the hallway with his friends, an unbothered smirk resting on his face. Later, you hear through the web that the dean took an extremely bold disciplinary approach and suspended him from exactly one day of school and the first quarter of his next basketball game. With a sigh, you decide that this resolution is better than nothing, even though Matt simply learned to be careful who he says slurs too, not why he shouldn’t say them at all. You never received an apology, and were rather told to take it upon yourself to avoid Matt. If a system of restorative justice had been implemented, maybe you, the victim, and Matt, the aggressor, would both have gained valuable conflict resolution skills, and a sense of closure.

The majority of high schools in the United States operate using a system of discipline called retributive justice. This concept focuses on foundations of established rules, and issuing punishment equivalent to the crime of the offender. Retributive disciplinary systems involve zero communication between students and staff when rules are established, as most schools operate under a decades old code of conduct. These codes may not address all of the student body’s needs as our word evolves to be more tolerant of others. For example, some codes may not be updated to classify the misgendering of a transgender person as bullying. Additionally, Abby Porter, author of “Restorative Practices in Schools: Research Reveals Power of Restorative Approach, Part I and II”, asserts that these conduct codes usually adopt “zero tolerance policies” and administer “authoritarian punishment” (2). When a student breaks an established rule, they are issued the correlated punishment, which is in most cases detention or suspension. An informative article titled “What Teachers Need to Know About Restorative Justice ” published by the educational group We are the Teachers, explores alternative methodology to retributive justice. This group asserts that the suspensions dealt under retributive justice “interrupt a student’s education and lead to further bad behavior” and “don’t provide kids with any skills for working through issues with others” (1). When a student is suspended, they are not taught the skills to make amends with their victim. The weight of teaching right and wrong is rather put on the aggressor’s parents, as the student is expected to return from their suspension exhibiting improved behavior. Oftentimes, this is not the case. The aggressor, represented by Matt at the beginning of this piece, returns without remorse, and their victim may continue not to feel safe in their school environment. These unresolved conflicts could be rectified if systems of restorative justice were implemented in high schools in the United States.

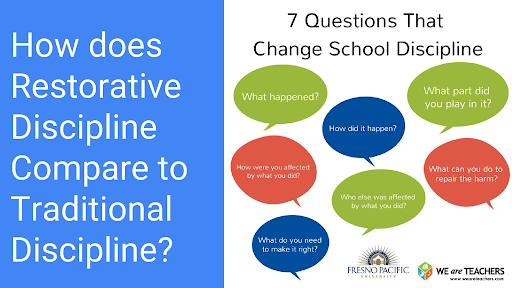

The We are Teachers group details the “three tier system” of restorative justice that focuses on “prevention, intervention, and reintegration” (5). The first tier is implemented at the beginning of a school year. Staff and students participate in an open forum in which they share what they believe should be included in a school’s code of conduct. This open discussion results in students taking ownership of the rules, as they helped establish them. The rules are seen as fair and reasonable, and the students sign a contract asserting they understand the policy of which they took part in creating (4). The second tier of restorative justice is implemented when a rule is broken. Typically an offender would be sent to a dean’s office where they would receive punishment, but tier two of a restorative system takes a different approach. The offender and the victim are encouraged to engage in a mediated conversation (5). The mediator can prompt the parties with questions such as “What specifically happened?” and “How can you repair the harm you caused?” (see figure in slides). If we were to use the previous Matt example again, Matt and his victim would meet. The victim and the mediator would explain to Matt why the slur he used is inappropriate and harmful. Matt could assert that he believes slurs are just words, which he can say because this is a two-sided conversation. This interaction does not act as a vessel to gain up on Matt, but as an open dialogue. The victim teaches Matt the history of the slur, and Matt begins to understand why what he said is harmful. He is given the opportunity to decide his own punishment, but after apologizing Matt is unsure as to what could make amends. The victim suggests that Matt attends a month’s worth of GSA meetings so that Matt can continue to learn about the LGBT community and gain the knowledge necessary to not hurt the community again. Matt agrees that this is a fair punishment. Tier three is not applicable to this example because mediation was successful and amends were made. In some instances such as extreme violence, suspension may still be applicable in addition to mediated conversation. This is where tier three becomes applicable. When a student returns from suspension, administration needs to provide the support necessary for a student to reintegrate into the school community. This may require additional attempts at aggressor victim mediation, or simply continued support regarding missed school work. Aggressors are less likely to re offend when they feel that the administration is not an enemy, but a support system who wants to see them succeed (6).

Abby Porter cites various studies in her paper that illustrate the success of implementing restorative justice in schools. The studies, conducted by Dr. Paul McCold, professor and lead researcher at the International Institute for Restorative Practices grad school, tracked behavioral offenses before and after various schools switched to restorative behavioral systems. One school who participated in the study reported a substantial decrease in bad behavior. The district stated that “detention, suspension rates, and incidences of aggression against teachers dropped” (15). They claimed that teachers experiencing threatening behavior dropped from 56 to 24 percent, and instances of physical assault dropped from 53 percent to 3 percent (15). These statistics are very promising, but many school districts are skeptical of restorative justice and cite a few drawbacks.

The We are Teachers group concedes that in order for restorative justice to work “engagement from all required parties” is required (27). If a student is unwilling to make amends with those they have harmed, the system is ineffective and the only resolution is typical punishment. However, one could infer that the vast majority of students would prefer making amends with their victim and agreeing on their own punishment, rather than suspension from school, sports games, ect. Another argument states that too much time and money is needed to implement restorative justice (28). This point is easily debunked, the main cost of implementing the program is training teachers and staff. Many free seminars and resources are available, especially online material found at restorativeresources.org, and even the cost of bringing in a professional is minuscule in the grand scheme of beneficial outcomes. The question of time constraints is a fair counter argument, but if the time needed to mediate conflict resolution results in less time spent on discipline during future conflicts, the cost is worth the reward. Even a slow integration of restorative practices can result in decreased behavioral incidents (see figure from We Are Teachers in slides). A 20 percent decrease in behavioral incidents could result from even a few teachers implementing restorative justice practices in their classrooms. Overall, the drawbacks of restorative justice are only temporary, and the reward eventually outweighs the cost.

Restorative justice disciplinary systems have been successfully implemented in many high schools across the state. How can we possibly continue to abide by our archaic code of conduct while other districts reap the benefits of restorative justice? Currently, students are suspended and return to school a day later with no remorse, and repeat offenders are rampant. Groups in our community, especially the LGBT community, do not feel heard as they never receive so much as an apology from their aggressors. No one in our community can properly heal until amends are made, and with mediated dialogue, students will become educated and empathetic humans. Restorative justice can become the solution to our massive behavioral problems, but only if we embrace it.

Works Cited

Davis, Matt. “Restorative Justice: Resources for Schools.” edutopia,

29 October 2015, https://www.edutopia.org/blog/restorative-justice-resources-matt-davis.

Accessed 16 January 2022

Porter, Abbey. “Restorative Practices in Schools: Research Reveals Power of Restorative

Approach, Part I.” International Institute for Restorative Practice Graduate School, 21 March 2007,www.iirp.edu/news/restorative-practices-in-schools-research-

reveals-power-of-restorative-approach-part-i. Accessed 16 January 2022

Porter, Abbey. “Restorative Practices in Schools: Research Reveals Power of Restorative

Approach, Part II.” International Institute for Restorative Practice Graduate School,

6 June 2007, https://www.iirp.edu/news/restorative-practices-in-schools-research-reveals-

power-of-restorative-approach-part-ii. Accessed 16 January 2022

We are Teachers Staff. “What Teachers Need to Know about Restorative Justice.” We are

Teachers, 27 July 2021,https://www.weareteachers.com/restorative-justice/.

Accessed 16 January 2022

Anna enjoys writing thought provoking articles and is also one half of the "Anna Show". She participates in volleyball, track, robotics, jazz band, GTV,...